My Great Grandparents, the Immortal Mulla Nasruddin and riding backwards into the future

Myself on the left holding a balloon, Grandmother Saltanat, the daughter of Sarah and Shemaaya and my sister Dary on the right

When Jules first heard that my mother came from Iran, his eyes glazed over with unbound fantasies.

His mind churned over all the wise stories and deep myths that originated in that culturally rich and ancient region that stretched from Turkey all the way to India and Persia, which was once called Aryana and nowadays is known as Iran.

“Are you sure that your family does not own a mulberry farm in the remote mountains, or a pomegranate orchard somewhere in Iran, that perhaps we could visit one day?….”

Jules asked me with much hope in his voice.

I assured him that to my knowledge, there were neither mulberries nor pomegranate orchards and that because they were Jewish, they barely escaped with their lives, holding on to their tiny and hungry children, and whatever jewelry they could hide in their garments.

Many years later, I have pieced together a rich tapestry of stories from that region, and my mother has added more color and spice, to the dark mist that was my personal history and roots.

I yearned to know more, and read many books and relished stories from that region.

A person can be truly enriched by LOOKING INTO THE PAST with loving eyes and with an open mind, thirsty for knowledge and wisdom.

The reason that I highlighted the words “LOOKING INTO THE PAST,” is because it is the very moral of the story that I wish to share with you here.

But allow me to start with my own roots.

As it turns out, my mother, Sarah, was named after my great grandmother.

My great grandmother Sarah was a very enigmatic woman who lived quite an interesting life.

She was given in marriage seven times, and every one of her husbands passed on.

She had children with some of these men, and she supported herself and her children by running her family’s collection of local Hammams.

Traditional Hammams, or bathhouses, are an integral part of life in that region.

People did not only go there to wash their bodies at the end of the working day; people often spent the whole day in the cavernous heat of the steamy Hammams, sharing news, gossip and neighborly stories, offering one another advice to handle life’s many hardships.

They also let the Hammam attendant knead their muscles and release all the pent up emotions that we normally store in our bodies.

Hammams, like the Japanese Onsens that I adore so much, are healing houses for achy bodies and tired and frightened souls.

When Jules and I visited Morocco, we visited many Hammams and loved leisurely spending our days there.

Because of their spiritual healing qualities, these bathhouses have survived in more or less their original form, throughout the millennia.

My great grandmother Sarah was finally matched to be married to a very short man named Shemaaya (“God Hears you”).

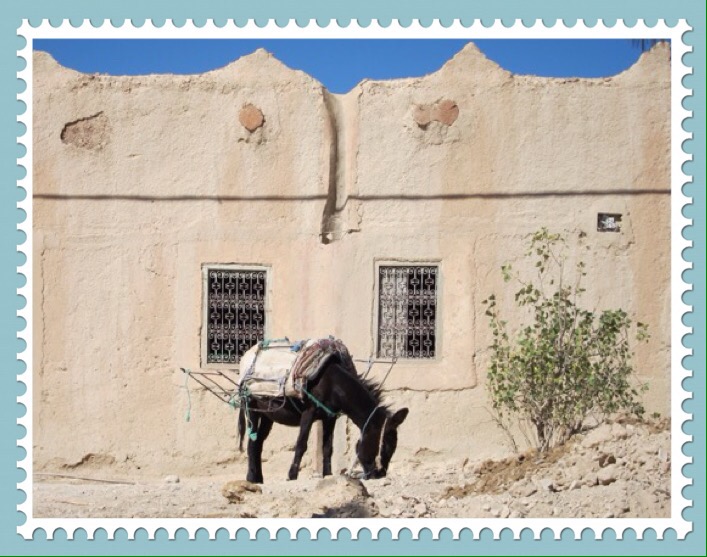

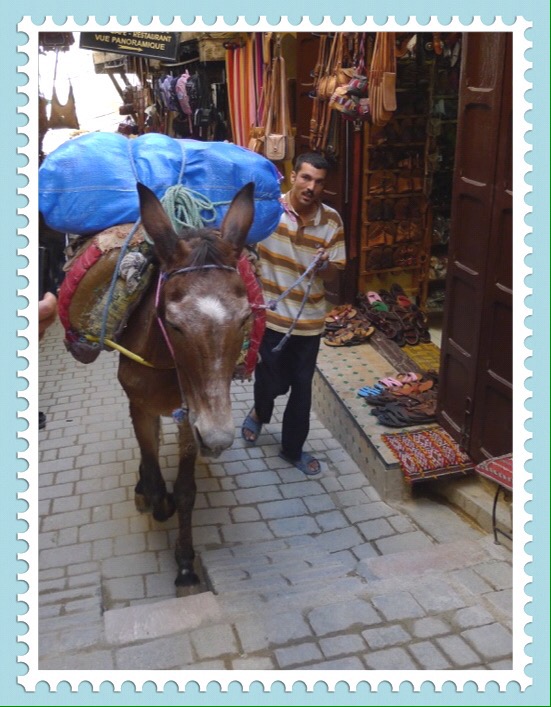

Baba Shemaaya was a trader who rode his donkey from village to village along an ancient trading route that ran all the way west to Iraq, selling goods that he carried in the satchels on his donkey.

They lived in Kermanshah, which is an ancient city west of Isfahan and about 525 km southwest of Tehran, at the foothills of the Zagros mountain range.

The languages spoken in that region are Kurdish, Laki and Persian.

Kermanshah enjoys a temperate climate and a full four seasons.

The summers are hot and dry with sudden gusts of hot wind that carry with them a fine desert sand that settles over everything,

During the springtime, the foothills of the Zagros mountains are covered in an array of colorful wildflowers.

In the winters, the mountains are covered in pure white snow and during the autumn, the leaves of the walnut trees turn red, and gusts of wind swirl across the old marketplace, where the merchants sell their goods from large sacks full of raisins and nuts.

It is the landscape of legends, of superstition, of love, of myths and passion, of intrigue and murder, of heartbreak and thievery, of shadowy jinns and the supernatural…

Sarah gave birth to my grandmother Saltanat.

In Kazakhstani and in Persian, Saltanat means a kingdom, a monarchy, celebrations, festivities, and triumph.

Saltanat gave birth to my mother, and as tradition dictates, she named her baby girl Sarah as well.

Saltanat did not like the name Sarah, because she believed that the name is loaded with a destiny of sorrow, that dates back to Biblical times.

The Biblical Sarah was married to Abraham and despite her exceptional beauty, she lived as a barren women for most of her life.

Saltanat’s own mother Sarah had lost all of her seven husbands, and was considered “cursed” and so was made to marry Shemaaya, who was barely tall enough not to be considered a midget.

But traditions are strong in those regions, and thus Saltanat was only able to add the name “Naeemah,” and thus my mother was known as Sarah Naeemah.

Most people called my mother Sarah, but her mother NEVER used that name.

With superstitious zeal, she called her daughter Naeemah, which is a name with an Egyptian and Arabic origin that means “A kind and benevolent woman.”

The image of my great grandfather Shemaaya riding on his donkey through the beautiful landscape has excited my artistic imagination.

It reminds me of paintings that I saw of Mulla Nasruddin, who is the subject of many wise folkstories from that region.

Mulla Nasruddin is claimed by the Turks, Afghans, Iranians, Uzbeks, Azerbaijanis, Turkmenistan, Indians and by the Arabs, as well as by the Turkic Xinjiang area of western China.

The truth is that all of them are right.

The Seljuk Empire in which he lived, rose to power in the 9th century, when it stretched from Turkey to the Punjab in India, as had the “Achmaenid Empire” a thousand years earlier, carrying with it enlightening stories from that region.

Most of the stories of Mulla Nasruddin are laced with humor.

In fact, for most of his early life, he was just a penniless wandering mendicant, roaming the countryside and marketplaces, behaving with good hearted foolishness.

Early stories recount that while he was sitting in the marketplace, people loved to make fun of him.

A story says that when he was given a basket of gold coins and told to have his pick, he would always take only the smallest and tiniest gold coin.

Once a kind man felt sorry for Nasruddin and told him:

“You know, you should take the bigger gold coins, they are worth much more and people will stop laughing at you.”

“Aha!…” said Nasruddin, “That may be true, but if I always take the larger coin, people will stop offering me money to prove that I am an idiot, and I would have no money at all.”

Stories say that after years of laughing at his expense, people finally realized how wise Nasruddin was and crowned him as Mulla, which means ‘A Master’ or ‘A wise teacher.’

They began asking for his advice in all matters of life, and often sought his counsel.

Mulla Nasruddin rose to fame, but he stayed humble and unpretentious, living a simple life.

Later in his life, he moved into the mountains, hoping to live a simple and isolated life, away from the foolish crowds who did not tap into their own inner wisdom, but ran to the wise Mulla with every little problem.

He chose to live far above a hill full of thorny bushes, hoping that the thorns would deter people from coming to him for advice at all hours of the day and night.

I read books full of stories about Mulla Nasruddin when I was a kid.

The Internet also has many tales told by many storytellers.

I discovered a fun website that is written as if the Mulla is the one speaking, and it is has an elegant and funny presentation of the original stories.

I will share here a story from this website.

It is called:

“It Is ALL God’s Will.”

“When I was no longer needed as a Mulla in the village, I moved to another region and found a convenient place outside a small town, on a hill.

The view was fine, and the hill was as thick with thorns and burdock as a peace-loving soul could want.

I was very happy with the thorns, because they discouraged agriculture.

In fact, they discouraged just about everything.

No one bothered me.

Eventually, however, my beloveds, this changed.

After a certain time, the townsfolk became curious.

They wondered what I was doing up on that hill, coming down only for a few groceries once in a while.

Anyway, the people began to come up the hill, through the thorns, until they made a path.

That made it easier for me to get down to the town, which was convenient.

It also made it easier for them to get up to me, which was not so convenient.

Somehow, the townsfolk came to view my silence and seclusion as a mark of wisdom.

And of course, whenever we admire something, we want to possess it.

I once saw a small knoll covered with wild blueberries, close to a pond.

The blueberry plants turned red in the fall, and the glorious color was reflected in the pond.

A family from a nearby town loved that blueberry field so much, they decided to build a house there.

They brought in excavators and heavy equipment, and tore out a large area on the top of the hill.

The runoff washed away many of the berries, and they piled building debris on a particularly beautiful patch, so that by the time their house was finished, they wondered where their idyllic little scene had gone.

That was how I was afraid I would be.

They would consider my seclusion to be admirable, so they would troop up to share it with me, until none of us was secluded any more.

One day, something happened that let me know I could preserve my seclusion in the long run.

A group came to me, much distressed.

“All our roosters have died!” they cried. “What are we to do?

We won’t wake up on time in the morning, and we won’t be able to eat chickens.

How will we live?”

Knowing the old saying that not a leaf turns except by the will of Allah, I looked at them for a long time. Finally they demanded an answer.

“It is all God’s will,” I said.

“God’s will?! Is that all you have to say?

What good does that do us?”

And they stalked down the hill, very dissatisfied.

However, my peace didn’t last for long.

Up they came again, with a fresh calamity.

“All of our fires have gone out!” they cried. “What will we do?”

“I suppose it wouldn’t help if I pointed out that you have no roosters to cook anyway?”

I said…

It didn’t help.

“What shall we do? We haven’t an amber or a coal in the village, and the next village is far away.”

I looked at them and shrugged. “It is God’s will,” I said.

“We thought you’d say that,” they muttered, and stalked off down the hill, very annoyed.

They were back sooner than I thought they would be.

“All our dogs have died!,” they cried.

“What other town is more unfortunate than ours? First our roosters, then our fires, now our dogs! Who will keep away wild animals, who will warn us of thieves?”

“Do you really have so many thieves?” I asked.

They admitted that nothing had ever been stolen in their village.

“I have only one thing to say, and I know that you don’t want to hear it,” I said.

“We know, we know… It is all God’s will.

That’s the last time we’ll ever ask YOU for advice!”

They said, and stormed off down the hill, very annoyed.

I hoped it was true.

But that very night, something occurred which I had been expecting.

I didn’t know exactly what to expect, but I expected something….

It was a little too much to have roosters, fires and all the dogs die, all at once in one little village…..

The night was totally dark, and I sat up and listened.

Around midnight, when all was quiet in the town below, I heard the sound of a large number of armed men approaching.

It was a marauding gang of bandits, looking to kill and loot.

Their general gave the signal for silence.

He stood listening carefully, looking down at the valley.

After a little time he spoke.

“Well, men, we have had a good run of it, going from town to town, pillaging and burning, and gathering as much treasures as we could find.”

There was a quiet clatter of spears and shields and shuffling of feet.

“But it looks as if there is no one in the village below.

Where is the smoke from the fires?

Where are the dogs barking?

It’s almost daylight, so where are the roosters crowing?

This village is abandoned.

Let us move on.”

So they turned back and went on their way.

The next day a few villagers came to see me.

“Have you thought of any solutions to our problems?,” they asked, “or are you going to say the same thing over and over?”

“You mean, that it is all God’s will?”

They nodded.

“Oh, I still believe it’s all God’s will, but I have something to add.

No matter how bad you think your problems are, they could always be worse.

Be content with what befalls you. It is truly sent from Heaven.”

To this day, they don’t believe me.”

(As written by Richard Merrill).

There is another famous story, this one about Mulla Nasruddin and the walnuts.

Nasruddin was riding backwards on his donkey, when the donkey got frightened by a mouse and started running, galloping through the marketplace like an insane ass.

The Mulla lost his balance and tumbled off, landing with a resounding crash right into the market-stand of walnuts, scattering the nuts everywhere.

Some small boys who had been nearby clustered around the walnut stand, laughing and pointing at Nasruddin, who appeared dazed, but unhurt.

“Why do you laugh?” Nasruddin snarled, “I was going to get off anyway, sooner or later.”

Everyone helped Süleyman the nut seller to collect the nuts and put the stand back in order.

Nasruddin bought a bag of walnuts to placate Süleyman, and to give to the kids to share.

“Children, I will give you all the walnuts in this bag.

But tell me first, how do you want me to divide the walnuts: God’s way, or the mortal human way?”

“God’s way,” said the four boys together as one.

Mullah opened the bag and gave two handfuls of walnuts to the first boy, one handful to the next boy, just two walnuts to the third boy, and none at all to the last!

All the children were baffled, but the fourth boy pouted and complained:

“What kind of nonsense distribution is this?”

“This is God’s way of distributing gifts among His children.

Some will get lots, some get a fair amount, and nothing at all goes to others.

Now, had you asked me to divide the nuts by the usual human or mortal’s way, I would have handed out an equal amount to everybody.”

The moral of the story is that not all of us come to earth to learn the exact same lessons.

Some of us need certain tools for our mission and others need other kinds of tools, in order to accomplish their own missions, thus we do not get the same gifts as we journey into life.

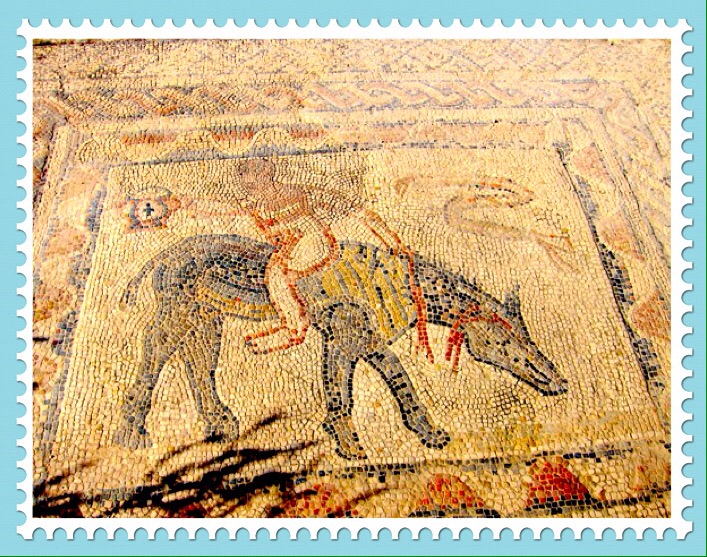

Perhaps the biggest conundrum about the Mulla is, “Why did the Mulla always ride his donkey facing backwards?…”

This story is a classic.

Nasruddin is always painted as riding backward on his donkey.

When asked why he travels backward, Nasruddin had many answers.

At times he denied that it was he who was facing in the wrong direction, and said that the donkey didn’t know where he was going.

Or that the donkey wants to go one way and he wanted to go the other way, and thus they made this “compromise…”

When people asked Nasruddin where he was going and how he thought he could get there by going backwards, he replied: “Don’t ask me, ask the donkey.”

People started seeing it as a symbol that the Mulla did not know where he was headed in life, and thus chose to ride backwards.

My favorite answer of Mulla Nasruddin is:

“It’s not that I am sitting on the donkey backwards, it’s just that I’m more interested in where I am COMING FROM, than where I am going to, my friends.”

I agree.

The future can only be imagined, but the past is clearly visible.

Each and every one of us can find deep and rich cultural stories like the ones I found in my roots, telling us much about where you have come from.

The TREE OF LIFE has many branches and very deep roots, and at our core, we are all one family.

We need to love and embrace one another’s cultures and beauty.

In New Zealand, the Maori have the term: “Ka Mura, Ka Muri.”

It says that the past is clearly visible in our memory, and that the future is unknown and thus unseen.

It is more correct to visualize the timeline of the past, present and future, as if the past is in front of us, while the unseen future is behind us and hidden from our field of vision.

We should walk backwards INTO THE FUTURE, with the past in front of us.

“Ka Mura, Ka Muri”

“Walking backwards into the future”

Trailblazing the future from the fires of the past.

It is a different concept of time, one that was commonly held by some ancient cultures.

We must not ignore the past, with its romance and sad traumas.

With new and loving, enlightened eyes, we must reinterpret what has occurred and step out of the victim mentality, to see why we ourselves have laid it out on our own path, in order to learn, experience and grow.

When I look deeply into the past and look at the original TREE OF LIFE, I find that my roots run tens of thousands of years into the past, way before there were any Jews and Muslims living on the earth.

In the recent past, both Jews and Muslims worshipped the same stories in the same Bible, and there were VERY FEW cultural differences between my Jewish family and their Muslim neighbors.

My great grandmother Sarah had five children in total.

All carried names that were common to that unique part of the earth, and many families, both Jewish and Muslim, gave their children those same names.

There was a boy named Aziz who had fair skin, blond hair and blue eyes.

Another boy who was called Morad,

My grandmother Saltanat,

A boy named Nostratola, whose name means “a messenger of God” in Persian, and who walked with a limp,

And a boy named Abdulla.

The history of the Jews in Kermanshah was not rosy,

Around 1827, there were 300 Jewish families living among 80,000 Muslims.

Most of the Jews were poor.

By 1860 there were fewer Jews left in Kermanshah, and it was reported that “they were not God fearing people.”

According to reports that were collected in 1884 when there were only about 250 Jewish families left, it was said that the “Muslims hated the Jews and that several Jewish families in Kermanshah had embraced the Christian or Bahai faith in the last half of the nineteenth century in order to survive.”

In March, 1909, there was a terrible pogrom against the Jews, in Kermanshah which resulted in Jews being killed or wounded, and the looting of all their properties.

My great grandmother Sarah lost her husband, Shemaaya.

She lived to a ripe old age as befitting her namesake, the Biblical Sarah, who lived to the age of 127, and is the ONLY woman in the Bible whose age is mentioned.

Nobody knows the exact age that my great grandmother Sarah reached.

At those times people gave birth not in hospitals, but in the privacy of their homes. They did not register their children, especially not the baby girls, and especially not the Jews, who lived in fear for their lives.

Sarah moved to Israel, thanks to one of the “Flying Carpets” missions that were sponsored by kind-hearted Jews who chartered planes to bring hunted and persecuted Jews from Yemen, and from all over the Arab diaspora, to find shelter in Israel.

My mother remembers that she used to visit her aging grandmother, and ask if she could do anything for her.

Since my mother was so handy with her sewing machine, she offered to make dresses for her grandmother.

Sarah always asked my mother to sew two pockets on the front of her dresses.

“One pocket for the past and one pocket for the future,”

Said the ancient grandmother, with a twinkle of wisdom in her eye….

*********************

Read more Nasruddin stories, wittily written by Richard Merrill at:

http://www.nasruddin.org/pages/storylist.html

Also : http://wandering4loveofgod.blogspot.com/2013_06_01_archive.html

********************

The photos of the floor mosaic of the Mulla riding backwards, we photographed while visiting the ancient Roman ruins of Volubilis in Morocco.

The ruins of Volubilis might date the Mulla as early as the 3rd. Century BC.